Absent

presence

Sirus walks through the city

“I arrived in Palermo in 1980 to study architecture at the University of Palermo.”

“In Perugia they warned me of the mafia, the underworld. That in Palermo you had to carry a knife because danger was lurking around every corner.

When I arrived I saw that there was this, and a certain arrogance, but I also warmed to the place, with all these familiar forms which connected me with my culture. And I thought: there is also beauty in Palermo!”

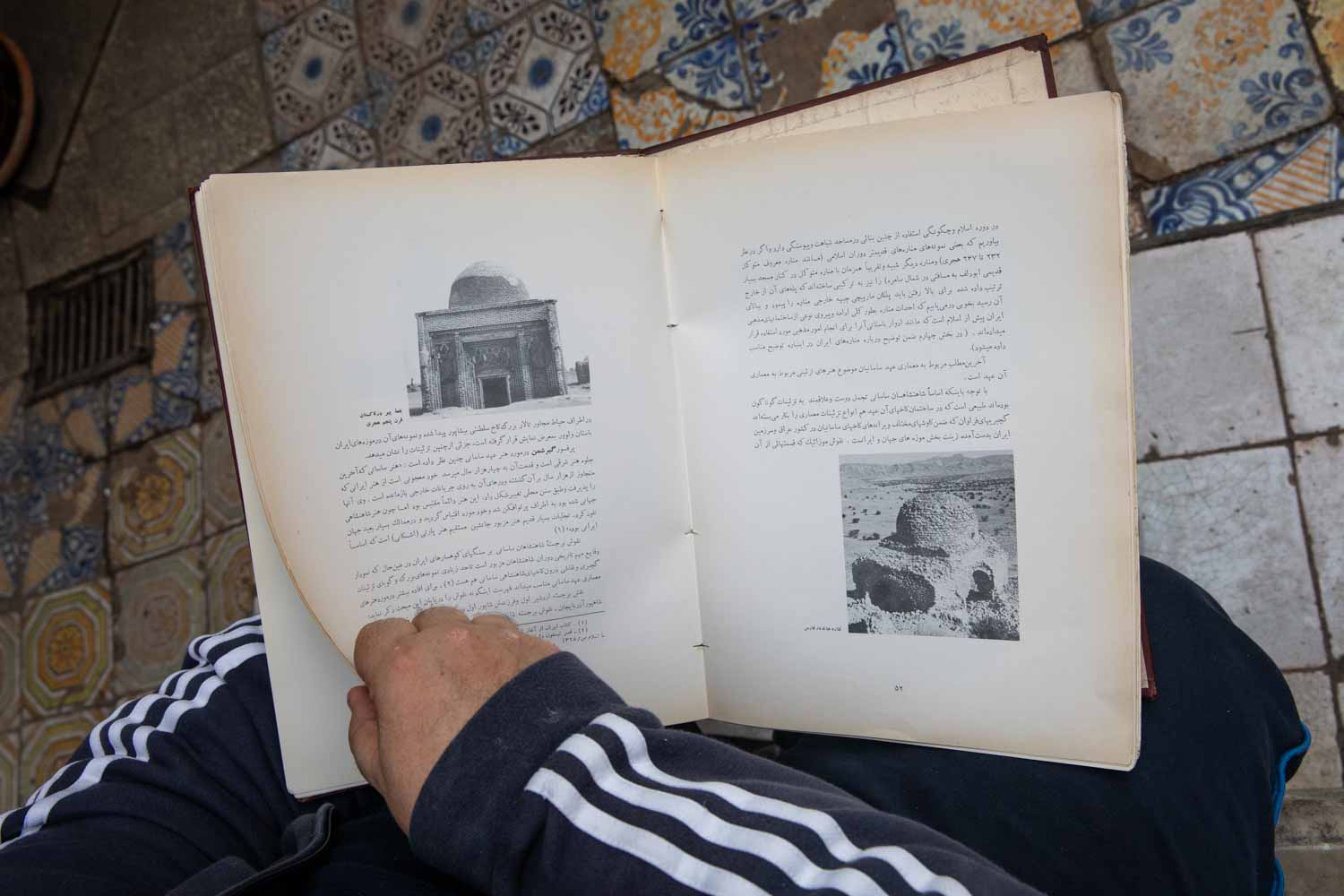

“When I discovered the monuments of Palermo, I saw traces of Persian culture that weren’t mentioned anywhere, and that no one knew about.

Inside the walls of the old town there were more than 300 mosques. The location of some has been found, but not of others.”

“The Normans used materials from the mosques to make churches so there is almost nothing left. Then with the arrival of the Spanish, much was destroyed.

Most of the monuments were abandoned. Cuba Palace was only recently opened as it had been inside a barracks, so no one could visit.”

“San Giovanni degli Eremiti... they sent me there to carry out surveys, the first year of my studies.”

“And as soon as I arrived, seeing these domes, it struck me.

These concave and convex shapes, and the muqarnas, I found them in palaces like Ziza or Cuba.

These shapes provided a cultural bridge between myself, my culture and this new land.”

“I tried to explain to others that behind that Arab Islamic culture there were 2500 years of Persian culture.”

“But it was presented as Arab or Arab-Norman... the Persian connection was missing, absent.

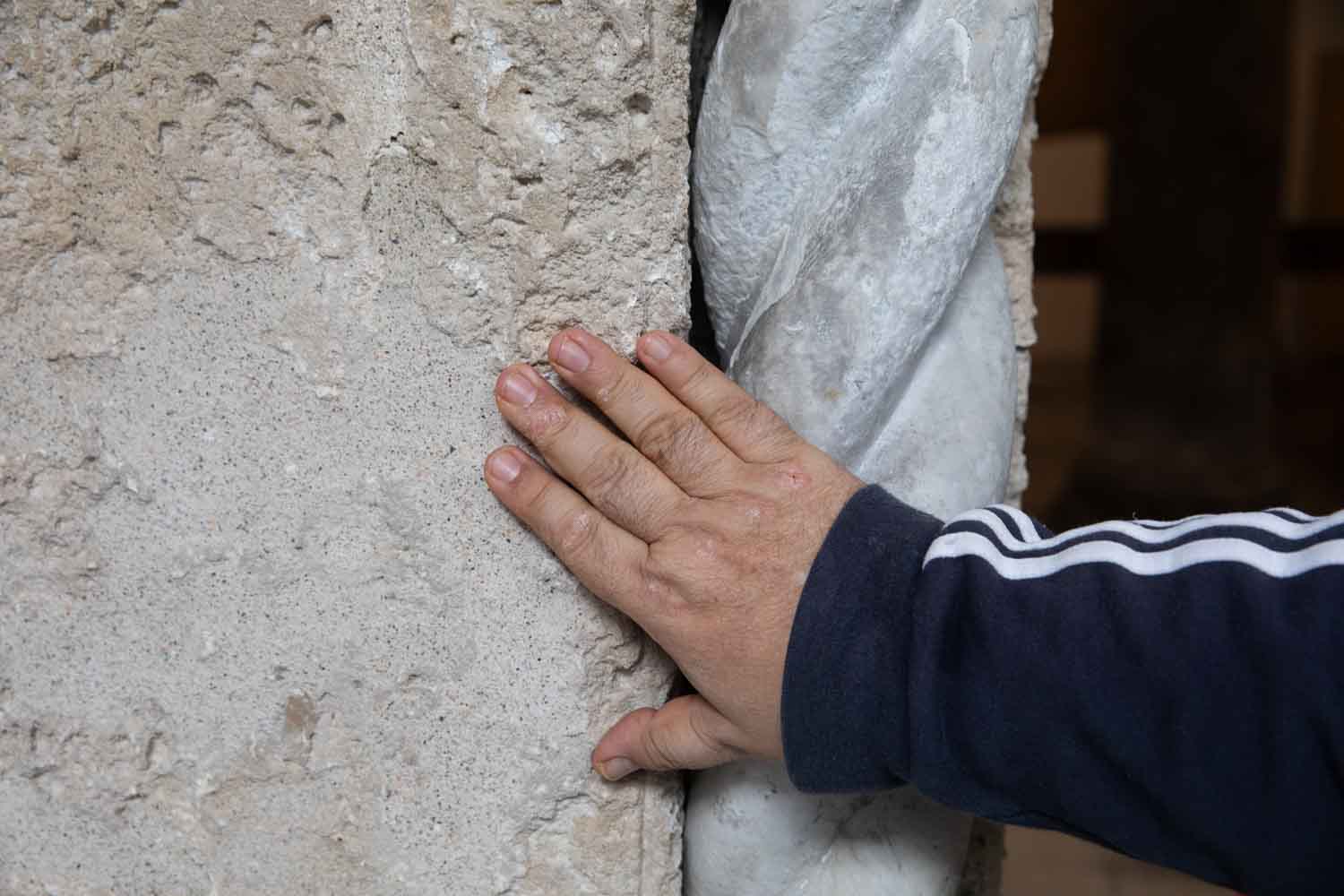

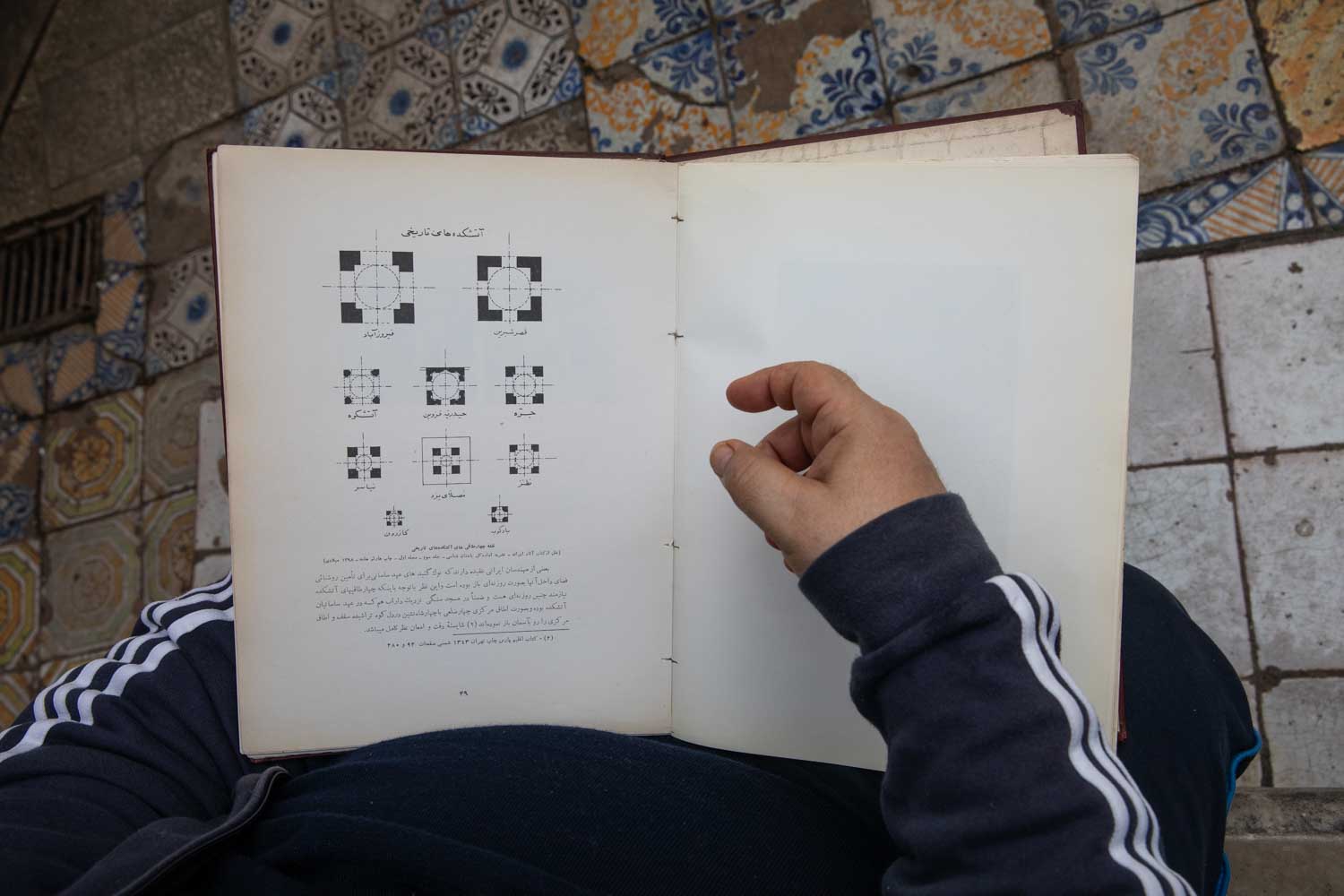

We used to come here, to see and touch the bases of these pillars, these former mosques. It was a square structure with four pillars and four arches covered by a dome.”

“And then the shape was replicated many times, side-by-side to make the whole mosque.

The moment the Arabs entered Persia they employed this architectural model as a basis for building mosques and inherited its symbolism.”

“Traditionally, the square stands for the earth, and the arches are open to four areas of the world.

The Arabs employed this model, taken from Persia, as a basis for buildings their mosques. And with it, it’s symbolism.“

But, in Islam God says that at the centre of Paradise is a fountain from which flow four rivers with water, milk, honey and wine.“

“Palermo has a qanat (aqueduct) system carrying water across the city in underground canals, connected to wells. This system arrived from North Africa to Sicily.”

“There was a well in San Giovanni degli Eremiti and when you threw stones you could hear them falling into the water.

We think it might have been the famous Papireto, the underground river… I saw it, I heard it.

In finding these architectural elements, I started to feel that Palermo was like home.”

“This land was part of my culture, and it motivated me to stay, explore and understand the city.”